Sardine Carrier For Sale – Sardine Carrier Boat Hull Plans welcome to your posting guys. Sardine Carrier Glenn-geary, Helen Mccall, Strathaven, İnterior Paint Color and more with you.

We have compiled all the technical specifications, old and new pictures, speed, engine and more of this precious boat for you. In this article you can find everything about this boat. In fact, we have left you the necessary contact information for purchasing. I highly recommend you to read this amazing article till the end.

Sardine Carrier For Sale

Sardine Carrier For Sale Near Me is a stunningly beautiful large sardine boat built in the Simms Brothers garden in Massachusetts. You can easily catch sardines and other fish with this boat.

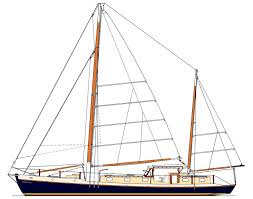

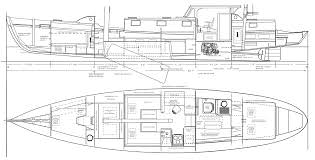

Sardine Carrier For Sale was designed with the comfort of a luxury home. In addition, these boats appeal to many audiences with their performance and practicality. PARTICULARS BELOW:

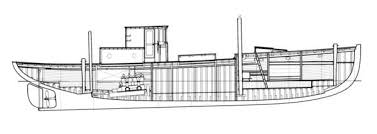

- LOA – 64’11”

- LWL – 60′ 10″

- BEAM – 12′ 6″

- DRAFT – 5′ 6″

- DISPLACEMENT – 70,000 lb.

- HULL TYPE – Sardine Carrier

- CONSTRUCTION – Single carvel planking over steamed frames.

- PROPULSION – 180 HP Detroit 671 diesel

- SPEED – Up to 11 kt.

- PLANS SHEETS – Various

- PLANS DETAIL – Above average

- PLANS COST – Contact Doug Hylan

OTHER REFERENCES – WoodenBoat 136 (page 99), 141 (page 80), 142 (page 78).

TO ORDER PLANS: For information about plans availability, please contact us at Hylan & Brown – Boatbuilders, 53 Benjamin River Dr. Brooklin, ME 04616 or doug@dhylanboats.com.

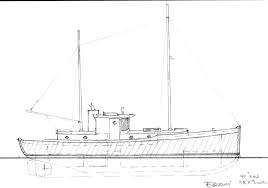

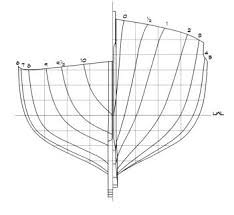

Sardine Carrier Boat Hull Plans

Sardine Carrier Boat Hull Plans below.

- Scratchbuilt Sardine Carrier (Hull No. 2)

These boats were built with three considerations in mind:

1) To be handled slowly and easily by young children.

2) They are almost unsinkable.

3) It should be produced as cheaply as possible.

The plans of this boat are in pretty good shape for these criteria. Professional, practical and quite safe. This is H.H. It will fully illuminate the production of the Mowgli, an 85th Atlantic sardine ship based on Payson’s “Pauline” plans:

This built model also has the super feature of being powered by a direct-drive 14V Pittman motor that spins a 1/32 scale and 31″ long! 1.5″ propeller. Power is provided by the 7.2 V 3300 MAH NiMH battery pack. The radio is a basic 2 channel AM Tower Hobby system.

Sardine Carrier Amaretto

Sardine Carrier Amaretto details are below. A traveler’s original plan during the winter of 1976-77 was to make some money by shipping herring in Penobscot Bay. Later (about a year later), his goal was to remove the 1930s Buddha diesel and replace it with something more reliable. However, it did not.

Sardine Carrier Glenn-geary

Sardine Carrier Glenn-geary details below.

- Title:

Sardine Carriers Glenn Geary and Helen McColl at Southwest Boat Corporation Dock in Southwest Harbor

- Type:

- Subject:

Structures, Transportation, Marine Landing, Wharf

Vessels, Boat, Sardine Carrier

- Creator:

Ballard – Willis Humphreys Ballard (1906-1980)

- Address:

168 Clark Point Road

- Place:

Southwest Harbor

- State:

ME

- Country:

USA

- Source:

Collection of the Clark Family

- Rights:

Helen Mccall Sardine Carrier

Helen Mccall Sardine Carrier details below.

- Title:

Helen McColl – Sardine Carrier

- Type:

- Subject:

Vessels, Boat, Sardine Carrier

- Description:

The “Helen McColl” was named for the daughter of the Seacoast Canning Company manager, Francis P. McColl.

“The vessel “Helen McColl” “was often referred to as the “Queen” or “Flagship” of the Seacoast [Canning Company] fleet. She had fine lines, was long and narrow with two masts and no wheelhouse.” She was similar to the “Mildred McColl” built in 1913 and named for Helen’s mother, Mary Permelia “Mildred” (Smith) McColl.

She was originally built [in 1911 by the Adams Ship Building Company at East Boothbay, Maine as a “knock about” schooner to be used to freight lobsters from Nova Scotia to Boston.

Sardine Carrier Beryl Camden

Sardine Carrier Beryl Camden next time. Other details can be found below. Please continue reading. sardine carrier for sale.

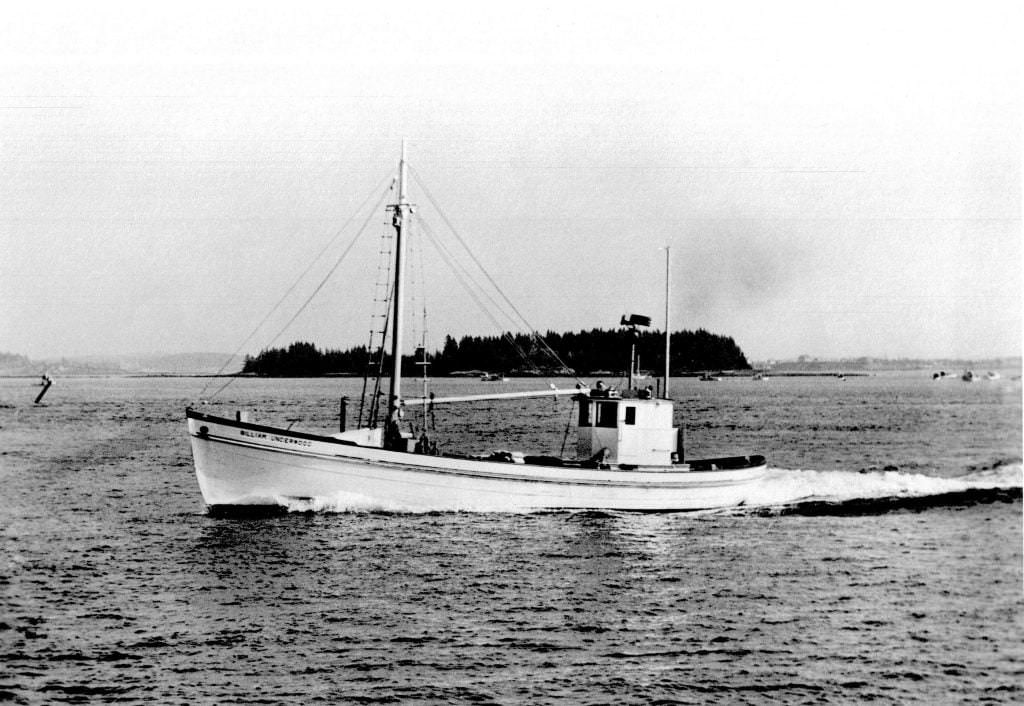

Sardine Carrier Called Satellite

Sardine Carrier Called Satellite: Taylor Allen saw William Underwood for the first time a long time ago at the Atlantic Shipyard at Brooklin/Flye Point in Herrick’s Bay! The old sardine ship, built in 1941, had been partially remodeled – in fact, the boat had been stripped down to its hull and had been under cover for some time.

Sardine Carrier Strathaven

Sardine Carrier Strathaven= Roger Eldon Kinghorne of North Head Grand Manan Island passed away at his camp at the Logan Hole Monday February 7, 2011. Born in 1955 he was the son of Mr. and Mrs Lawson and Ethel Kinghorne of North Head.

Roger worked hard as a fisherman all of his life. He owned and operated his lobster boat “Special K”, worked for Connors Bros. on the sardine carrier “Strathaven” for the past several years, fished for sea urchins, scallops, and worked in the weir fishery as well over the course of his career as an inshore fisherman.

Song Man Dies On Sardine Carrier Gordon Bok

Song Man Dies On Sardine Carrier Gordon Bok pdf is below. Download please.

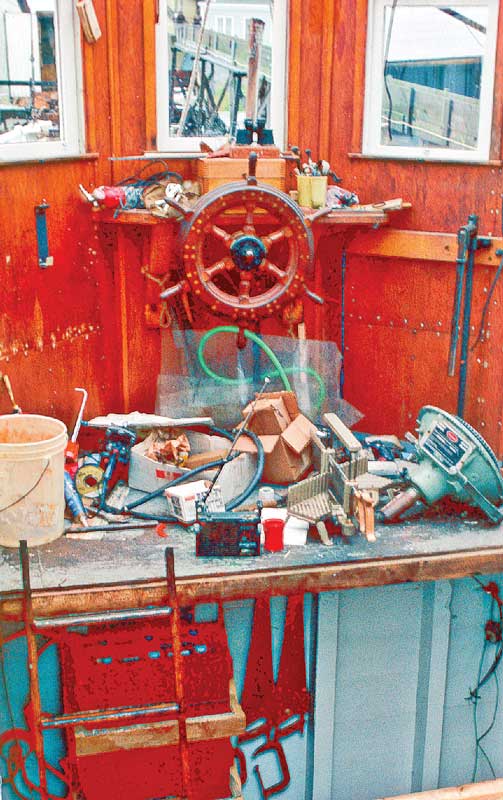

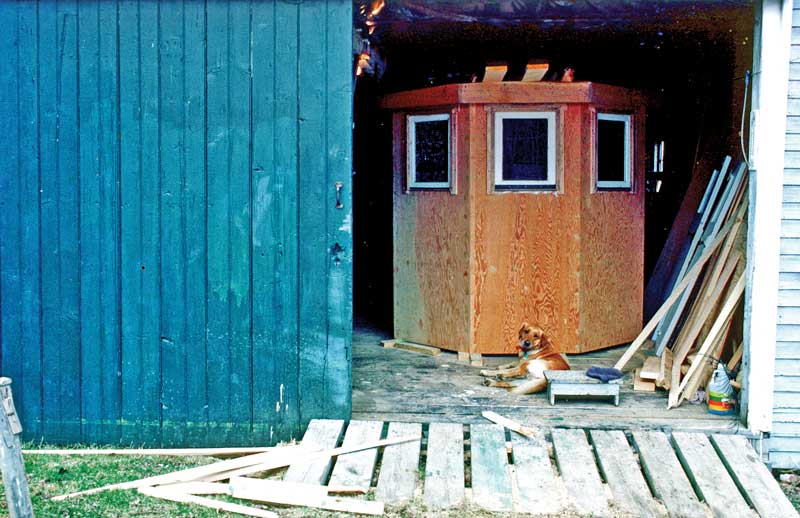

Grayling Sardine Carrier İnterior Paint Color

Grayling Sardine Carrier Interior Paint Color: At Thomas Townsend Custom Woodworking in Mystic, Connecticut, walls are painted a warm buff color and covered with poster-size black and white photographs of family boats, vintage trawlers and old advertisements for lobster boats.

Townsend remodeled the Penbos as simply as possible, replacing many of the original deck furniture and hatches with their own versions, and replacing the hinged doors to the deckhouse with sliders to eliminate visual breaks in the sides of the house.

Bluejacket Models Sardine Carrier

Bluejacket Models Sardine Carrier details. Someone set out to build the sardine ship Pauline by Bluejacket Shipcrafters.

The story of someone who, after spending time traveling between Portland and Mount Desert Island off the coast of Maine, by both car and boat, encounters a variety of ships and boats.

Duryea+sardine Carrier+satellite

Duryea+sardine Carrier+satellite are below:

The Mary Anne was built for the Holmes Packing Company of Eastport, owned by Moses Pike of Lubec. It was the first refrigerated sardine carrier, bubbling chilled salt water and air up though the hundred-ton load of herring that the vessel could carry.

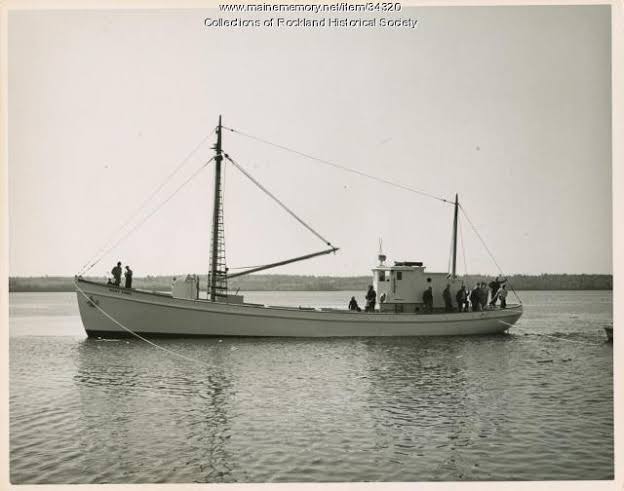

About This Item

- Title: Sardine carrier Mary Anne afloat, Thomaston, 1947

- Creator: Sidney L. Cullen

- Creation Date: 1947

- Subject Date: 1947

- Location: Thomaston, Knox County, ME

- Media: Photographic print

- Dimensions: 19.5 cm x 24.8 cm

- Local Code: Pike 12

- Collection: Anne Pike Rugh/Rockland Courier Gazette collection

- Object Type: Image

Vintage Sardine Carrier Photos

Vintage Sardine Carrier Photos is below;

New Bruswick Sardine Carrier

New Bruswick Sardine Carrier details. sardine carrier for sale. Blacks Harbor, one of the world’s largest processors of sardines, is located in New Brunswick, Canada. While the documentary was being filmed, the adventure in a Herring Carrier involved witnessing how they ‘bag and purse’ the Herring and bring it back to the factory so that they could ‘make’ the prey. We hope to share all the details about this subject in video form. You can stay tuned.

Coastal Forces Ho Scale Sardine Carrier/coaster Kit #9611

Coastal Forces HO Scale Sardine Carrier/Coaster Model boat. Resin Casting, nicely detailed, metal and wood parts , Excellent instructions Shipping by Priority Mail, $9.00. Go to do Coastal Forces Ho Scale Sardine Carrier/coaster Kit #9611.

Rebuilt from the spine. 199036-mile color radar. Satellite compass with AIS color siren. Autopilot and clock alarm!

- Asking Price: $225,000

- Length of Hull: 70′ (21.34 meters)

- Load Waterline Length: 65′ (19.81 meters)

- Beam: 20′ (6.10 meters)

- Draft: 8′

- 6″ (2.59 meters)

- Engine/Power: 400 HP Deawoo

Street Address: Owls Head

Owls Head

Maine

United States

Email: dbleagle@roadrunner.com

Contact Information

| Contact | İnformation |

|---|---|

| Phone: Fax: | (207) 236-7048 (207) 230-0177 |

Please Add a comment before the calling of Newbert Boats, we will inform your mail address to the owner of the boats. They will reach you by email or phone.

Song Man Dies On Sardine Carrier

Curious about Song Man Dies On Sardine Carrier? We would like to inform you about this issue. But we are not aware of such an event. Therefore, we would like to update it as soon as possible.

Newbert & Boats for Sale Craigslist & Newbert & Specs & Pictures

listed in this advert.

Explore full detailed information & find used Newbert & boats for sale near me.

®️Numberoneboats.com Leader Platform For Sale Boats & Yachts.

For more related Newbert & Wallace Boats, please check below. We have totally 300.000 model Newbert Boats on our website. sardine carrier for sale ad is over.

What is the Price of Sardine Carrier Boat?

Sardine Carrier price ranges from $22,500 to $1,150,000.

Do Sardine Carrier Boats have another name?

Another name for Sardine Carrier Boats is Newbert & Wallace.

You may also like these boats and yachts for sale:

Number One Boats from USA. Boat Marketplace Group Network. All Boats & Yachts for Sale, Reviews, Specs, Prices, Craigslists.

Number One Boats from USA. Boat Marketplace Group Network. All Boats & Yachts for Sale, Reviews, Specs, Prices, Craigslists.